Expanding the men’s NCAA tournament field has been discussed each February for the past three years. One common objection to expansion is that the new spots in a larger bracket will go mostly if not entirely to so-called mediocre teams from major conferences at the expense of mid-major programs.

If the NCAA does adopt a larger bracket and the NCAA men’s basketball committee does start favoring major-conference teams at the expense of mid-majors, those who want to keep the field at 68 will have been proven correct. Both halves of this scenario could come to pass. Stranger things have happened.

The key words in this scenario, however, are “does start favoring.” Since the field expanded to 68 teams in 2011, the selection committee has in fact compiled a notably even-handed track record in awarding at-large bids to both major-conference programs and mid-major teams when controlling for KenPom rank.

Granted, this even-handedness can be difficult to spot in real time. Of the 12 teams left out of the tournament over the past three years as members of the “first four out” list, for example, just two were mid-majors (Dayton in 2022 and Indiana State last year). Pegging the field’s size at 72 teams prior to the 2022 bracket would indeed have given us 10 more major-conference teams over the past three brackets just like critics of expansion say.

Then again over that same three-year span mid-majors earned no fewer than 17 at-large bids. Even that number for at-large invites would surely be higher if not for the fact that eventual 2023 Final Four teams San Diego State and Florida Atlantic both won their conference tournaments, as did a nascent No. 7 seed like Murray State in 2022. Lacking greater representation on the “first four out” list isn’t necessarily a bad thing for mid-majors.

In addition to counting how many mid-majors are just missing 68-team brackets, we can consider the performance of these programs in competing for all 36 at-large bids. Say you’re ranked in the top 90 at KenPom on Selection Sunday. Do your chances for an at-large bid improve in relation to your same-tier peers by virtue of major-conference membership alone?

Not really. Controlling for KenPom rank, selection rates for major-conference and mid-major at-large candidates have been notably similar since the field expanded to 68 teams in 2011. The challenge for mid-majors, of course, is breaking into these lofty tiers in the first place. Once they do, however, their chances are roughly equivalent to those of major-conference programs.

Mid-majors can compete in the committee room if they hit the top 60

Percentage of eligible teams receiving at-large bids by KenPom tier, 2011-24

% of eligible teams

receiving at-large bids

Nos. 1-30

Major-conference 98.0

Mid-major 96.4

Nos. 31-60

Major-conference 56.7

Mid-major 53.4

Nos. 61-90

Major-conference 5.9

Mid-major 3.9

Selection Sunday (pre-tournament) KenPom rankings

The structural impediment facing mid-majors isn’t invidious discrimination by the committee as much as it is funding, visibility, player (and coach) retention, and a resulting numerical scarcity at the top of D-I. At this writing 92 percent of the 2025 AP top 25 comes from the major conferences.

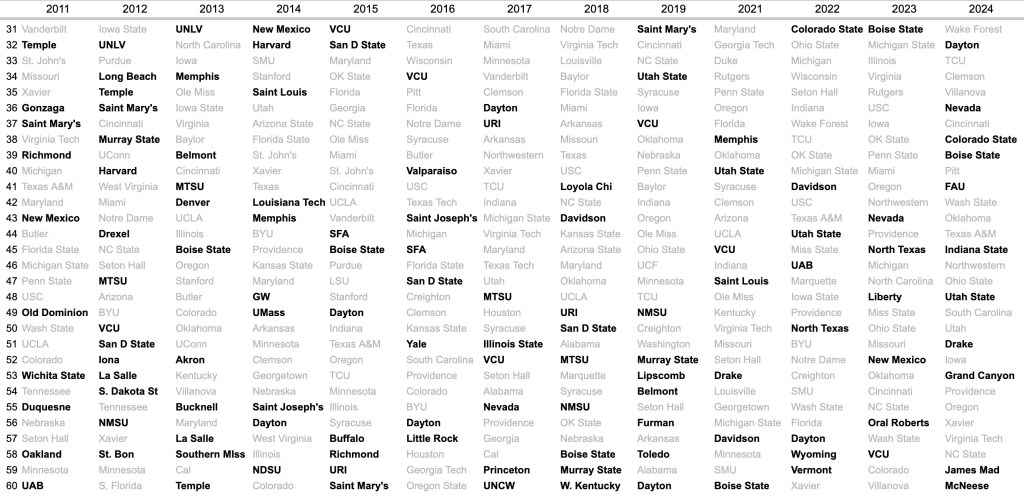

Mid-majors not named Gonzaga have long been scarce at the top of the sport, a scarcity that’s perhaps best conveyed visually. Here’s Ken’s top 30 on Selection Sunday from every year when there’s been a tournament since 2011. Mid-majors are in boldface. These programs have made up 17 percent of this top tier over the last 13 tournament seasons.

Conversely if we drop down to the next tier and look at teams ranked between 31 and 60, mid-majors have been almost twice as numerous (32 percent).

Since 2011 the committee has doled out at-large bids to major-conference teams and mid-majors alike in a mostly equitable manner. The population the committee considers each March, however, is brimming with major-conference powers. Expanding the bracket would put more teams from the 31-to-60 tier in the tournament and improve the selection odds for mid-majors compared to probabilities they face today.

The scales of the sport and its championship event favor the major-conference programs and will continue to do so if the field expands to 72 or 76 teams. Factors like “mid-major population between Nos. 31 and 60 at KenPom” will vary greatly year to year. Nevertheless. any additional at-large bids beyond the current 36 would tend over the long run to lessen ever so slightly the extremity of the bracket’s preference for major-conference programs.