Division I men’s basketball in 2025 is marked by superlatives. Scoring has never been more efficient. Shooting from the line has never been more accurate. Shot volume has never been higher. And, yes, official reviews have never been more numerous, lengthy, or maddening. The final minute of a close NBA game can offer a fitting crescendo of drama and action. The same portion of a D-I contest is far more likely to feature inaction.

Happily we have every reason to believe this era of endless trips to the monitor will soon end. On balance — and with the totemic and potentially existential exception of the manner in which teams qualify for the championship event — the NCAA over the last decade has been on an incredible run of precision meliorism. Decisions made over that span by the men and women in Indianapolis have made the game much better.

True, there have been bumps along that road. As of 2013 scoring was low and D-I’s tempo was lethargic. This first problem was addressed by calling more fouls in 2014. Scoring soared along with boredom. No one’s here to see free throws.

In retrospect 2015 really marked the beginning of better times. Kentucky’s 38-game pursuit of the sport’s first perfect season since 1976 coincided with a drop in whistles across D-I. Shaving five seconds off the shot clock the following year has locked the sport in around 68 or 69 possessions per 40 minutes ever since. (Possibly the international standard of 24 seconds would be even better than 30. Well, go fight City Hall. Quarters would be better than halves and the men have been waiting for those since 1954.)

The three-point line was then pushed out to the international distance prior to the 2019-20 season. This change reduced accuracy from beyond the arc but also created better spacing inside it. Today D-I is making an all-time high 51 percent of its twos.

By the time the NCAA revised the block/charge rule prior to last season, the pieces were really coming together. Now here we are.

Defenders are no longer rewarded for staging collisions. Foul rates are under control and little noticed. Effective field goal percentages are attaining 2019 levels even with the more challenging three-point line. There’s never been a better time to play offense. As a result the best offenses of 2025 rate out exceptionally well historically speaking.

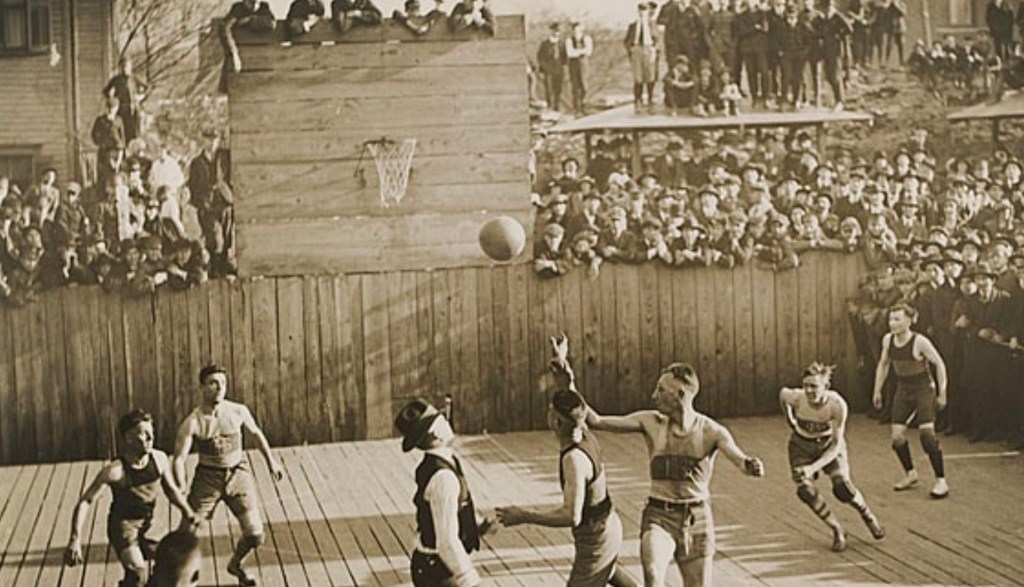

Of course they do. Today’s offenses are inheriting 135 years of trial and error and adjustment. College basketball had its own statistical equivalent of baseball’s dead-ball era. Now we too have stats that look very different.

Feel free to refer to these 2025 offenses as among the best “ever” (since 1997) at KenPom. These teams tend to score more points in fewer schedule-adjusted possessions than did their predecessors. But are these 2025 offenses truly among the best ever? Now we’re talking plumbers and firefighters. This is sports. We can all curate our own AP poll of the mind or our own Hall of Fame inductees. I can only speak for my rankings and selections.

If you want to be my choice for the greatest offense ever, I ask that you be the best offense in your conference. That’s just me. At this writing the offense with the highest adjusted efficiency ever ranks third in its league for points per possession in conference play. Show me more. I’m persuadable!

Until recently this trend toward better offense didn’t appear to be driving any similar movement toward stronger overall teams at the top of the standings. Now, however, this state of affairs may be changing. Following a precedent set by UConn last season, the consensus clear top two of 2025 also rank among the top 15 of all-KenPom-time for adjusted efficiency margin.

If it really does occur (there’s basketball still to be played in 2025) seeing three such teams in the span of two seasons would be a first in the 21st century. Possibly that’s pure chance.

Alternately, who knows, maybe we’re on the brink of a new age of mighty all-around teams that, unlike the best programs from previous eras, can score like nobody’s business. That would be fun!

In this new golden age we would get to have our one-and-done cake and eat it too. Yes, Cooper Flagg is still required to drop by for one season of college ball, but the sport as a whole is trending old. D-I this season still includes a player five months older than Luka Doncic.

One might expect two pandemic-era decisions by the NCAA to have significant downstream consequences. Allowing players to transfer more freely and to play (seemingly) forever could result in an older and thus better talent pool and for a more frictionless allocation of those players according to their own wishes. If so, such a development could, somewhat paradoxically, feel like a blast from the past.

Contrary to our trend for offense, going way back in time at KenPom produces a higher concentration of mighty teams above +34.00 for adjusted efficiency margin. From 1997 through 2002 there were no fewer than six such teams. Conversely from 2003 all the way through the ill-starred 2020 season there were just three: Kansas in 2008, Kentucky in 2015, and Virginia in 2019. (So the Cavaliers really did touch greatness?)

Maybe letting players stay forever while enjoying greater mobility across programs will turn out to be a cheat code for creating mighty teams in (relative historical) abundance. These new-era juggernauts will put far more points on the board. While playing 10-minute quarters. With limited official reviews. We can dream.